Acetylcholine regulates blood flow, but the source of blood acetylcholine has been unclear. Now, researchers at Karolinska Institutet have discovered that certain T cells in human blood can produce acetylcholine, which may help regulate blood pressure and inflammation. The study, which is published in PNAS, also demonstrates a possible association between these immune cells in seriously ill patients and the risk of death.

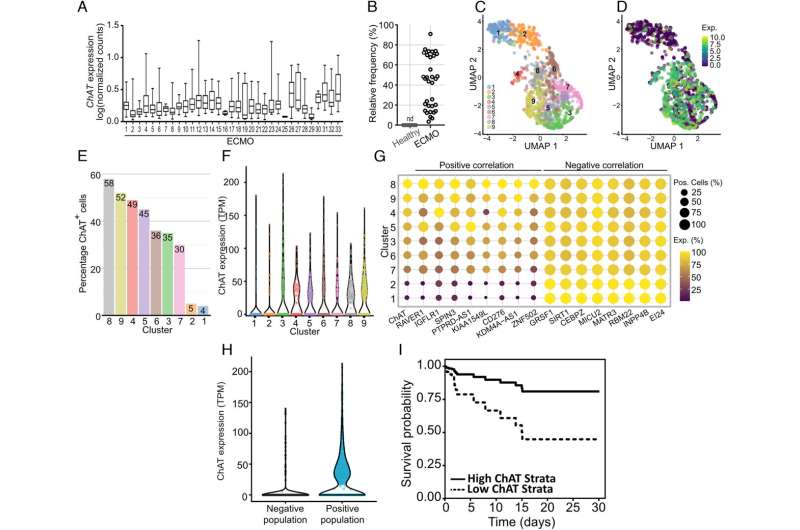

Blood flow regulation by acetylcholine is long established and highlighted by the 1998 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Yet the sources of acetylcholine in human blood have been unclear. Previous research, such as studies by Peder Olofsson’s group at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, has shown that a certain type of immune cell known asChAT+ T cells can produce acetylcholine and affect endothelial cells in the blood vessels of mice. However, it has not been known if these types of T cells exist in humans.

“We now show that human T cells can also release acetylcholine,” says the study’s joint first author Laura Tarnawski, assistant professor at the Department of Medicine (Solna), Karolinska Institutet. “This corroborates previous findings in different model systems and may contribute to the development of treatments for cardiovascular disease and inflammatory diseases.”

Acetylcholine also plays a vital role as a neurotransmitter in the brain and nervous system, but the researchers are particularly interested in its role in inflammation.

“We’re interested in how the brain communicates with the immune system, which is something we still know relatively little about,” says the other first author Vladimir Shavva, assistant professor at the same department. “Our new study shows that acetylcholine in the blood can be secreted by immune cells, which can regulate inflammation in the blood vessels.”

The findings are based on analyses of blood from healthy blood donors. The researchers also studied 33 patients with severe circulatory failure who had been admitted for intensive care, and found that higher relative blood levels of ChAT+ T cells were associated with reduced risk of death.

“Our findings are of clinical interest and could contribute to new diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities for seriously ill patients with excessive inflammation,” says principal investigator Peder Olofsson, senior researcher at the Department of Medicine (Solna).

The group now plans to map the presence of ChAT+ T cells in different patient groups and different organs, and how they affect metabolic and inflammatory processes.